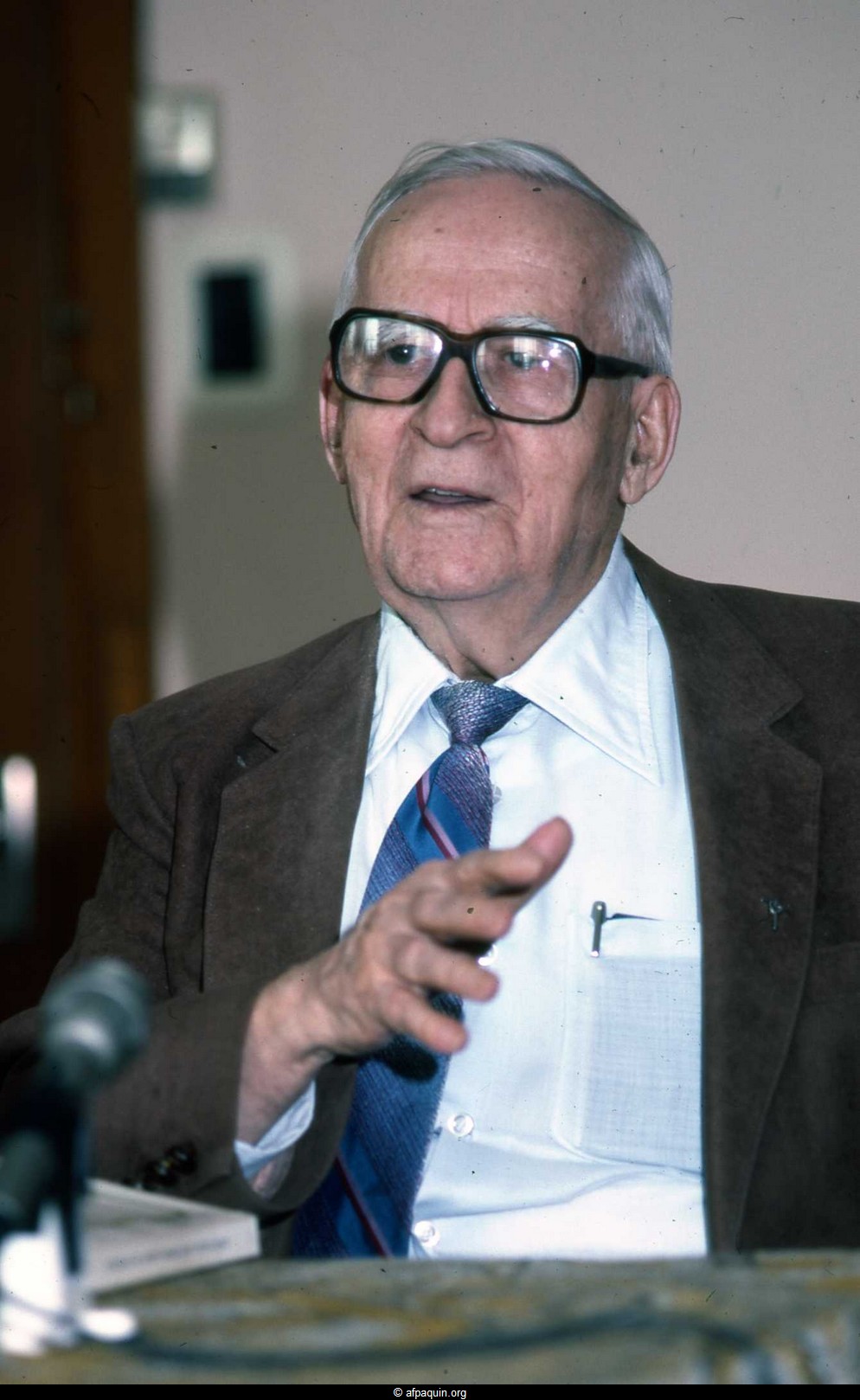

Brother Pasteur passed away. It was customary to see him at

see the large house of Sainte-Foy (formerly the provincial house of Quebec),

that it is difficult to get used to the idea of his departure. It seemed to us that he

would have lasted as long as the solid walls of this institution. And yet, age and infirmity took his toll. It was on the night of April 17 that his heart stopped beating. He had reached the respectable age of 95 years and 4 months.

Brother Pasteur was born on December 11, 1900, within a

family of farmers, in Saint-Tite, in the province of Quebec. His father, Silfrid, and his mother, Sarah Jacob, gave birth to 14 children, including seven boys and seven girls. Our late deceased was the twelfth. At his baptism he received the names of Joseph, Armand, Victor. It is under this last name that he

was known until his entry into the novitiate in April 1917.

Of his family and childhood, brother Pasteur had only good memories. He also loved his father and mother. They were good Christians, devout to the Sacred Heart and faithful to the practices of our holy religion. Victor was a good son within the family and, during the days off and during the holidays, willingly lent himself to the small tasks on the farm .

The F. Pasteur is no longer. We were so used to the

see the large house of Sainte-Foy (formerly the provincial house of Quebec),

that it is difficult to get used to the idea of his departure. It seemed to us that he

would have lasted as long as the solid walls of this institution. And yet, age and infirmity took his toll. It was on the night of April 17 that his heart stopped beating. He had reached the respectable age of 95 years and 4 months.

F. Pasteur was born on December 11, 1900, within a

family of farmers, in Saint-Tite, in the province of Quebec. His father, Silfrid, and his mother, Sarah Jacob, gave birth to 14 children, including seven boys and seven girls. Our late deceased was the twelfth. At his baptism he received the names of Joseph, Armand, Victor. It is under this last name that he

was known until his entry into the novitiate in April 1917.

Of his family and childhood, F. Pasteur had only good memories. He also loved his father and mother. They were good Christians, devout to the Sacred Heart and faithful to the practices of our holy religion. Victor was a good son of a family who, during the days off and during the holidays, willingly lent himself to the small tasks of the

closes.

It was in this happy family atmosphere that Victor gave birth to the aspiration to a life entirely consecrated to the Lord. His journey to religious life owes much to the example of his parish priest, father Jean-Baptiste Grenier. In August 1916 he entered the Arthabaska Juvenile Church, where his master was brother Désir. Brother David, his teacher, helped him a lot in his first steps away from his family.

The year 1917-1918 was that of his novitiate, under the good direction of Brother Albertus. There, he had as professor brother Alphée. From his novitiate, btother Pasteur had only good impressions; it was because he had accepted the training that was then given there.

It was in this happy family atmosphere that Victor gave birth to the aspiration to a life entirely consecrated to the Lord. His journey to religious life owes much to the example of his parish priest, M. l'abbé Jean-Baptiste Grenier. In August 1916 he entered the Arthabaska Juvenile Church, where his master was F. Désir. F. David, his teacher, helped him a lot in his first steps out of the family.

The year 1917-1918 was that of his novitiate, under the good direction of F. Albertus. There he had as professor F. Alphée. From his novitiate, F. Pasteur had only good impressions; it was because he had accepted the formation that was then given there.

Brother Pasteur was no ordinary personality. He

had good judgment, clear thinking and well-thought-out principles. There was in

him a set of qualities that attract confidence. He was honest and sincere,

and also an enemy of evasion. He had a strong sense of duty and carried out his duties

with fidelity and continuity. All his life, he was a hard worker.

His life was based on a set of certainties

from which he did not depart. Also, when the great upheavals of the 1960s,

brought about by a rapid cultural and religious revolution, he struggled to

follow and suffered greatly. Being a strong man, he held his ground on more

than one point. It was difficult to remove him from his positions. For, it must

be said, he was a gentle stubborn man with whom it was not easy to dialogue.

Here we touch on a point that can explain why

he had so few close friends. Undoubtedly, he had the qualities that gain

esteem, but these same qualities with too well-defined contours can offend.

Always sure of himself, brother Pasteur consulted little his entourage. If he had

more doubted himself (or pretended to doubt), and had taken the advice of his

confreres, he would have won their sympathy.

The F. Pasteur was no ordinary personality. He

had good judgment, clear thinking and well-thought-out principles. There was in

him a set of qualities that attract confidence. He was honest and forthright,

an enemy of evasion. He had a strong sense of duty and carried out his duties

with fidelity and continuity. All his life, he was a hard groper.

His life was based on a set of certainties

from which he did not depart. Also, when the great upheavals of the 1960s,

brought about by a rapid cultural and religious revolution, he struggled to

follow and suffered greatly. Being a strong man, he held his ground on more

than one point. It was difficult to remove him from his positions. For, it must

be said, he was a gentle stubborn man with whom it was not easy to dialogue.

Here we touch on a point that can explain why

he had so few close friends. Undoubtedly, he had the qualities that gain

esteem, but these same qualities with too well-defined contours can offend.

Always sure of himself, F. Pasteur consulted little his entourage. If he had

more doubted himself (or pretended to doubt), and had taken the advice of his

confreres, he would have won their sympathy.

Brother Pasteur taught for 25

years. As a holder of the Higher Education Certificate, he possessed his

subjects well and knew how to make his students succeed. He himself told me

that one day he was called upon to replace a colleague who had failed. He

therefore enters the classroom, and a pupil takes it upon himself to introduce

his classmates, whom the previous teacher had divided into three groups:

"These, he says, are the "niochons" (stubborn), these are the

lazy ones and this one is the leader of the lazy ones; These others are the

workers, and this is their leader." As a good pedagogue, brother Pasteur

quickly understood that such a classification was counter-indicated (today it

seems that it was contrary to human rights!). So he says to the students:

"Put yourselves all around the class in order of magnitude and we will

give you new places."

For the last two years as a teacher, brother

Pasteur spent them at École St-Esprit in Quebec, where he taught manual labour.

He had taken the courses then being held in Limoilou under the direction of brother

Georgius and had become competent in this field. This was to serve him later in

the various works of the provincial house.

The F. Pasteur taught for 25

years. As a holder of the Higher Education Certificate, he possessed his

subjects well and knew how to make his students succeed. He himself told me

that one day he was called upon to replace a colleague who had failed. He

therefore enters the classroom, and a pupil takes it upon himself to introduce

his classmates, whom the previous teacher had divided into three groups:

"These, he says, are the "niochons" (stubborn), these are the

lazy ones and this one is the leader of the lazy ones; These others are the

workers, and this is their leader." As a good pedagogue, F. Pasteur

quickly understood that such a classification was counter-indicated (today it

seems that it was contrary to human rights!). So he says to the students:

"Put yourselves all around the class in order of magnitude and we will

give you new places."

For the last two years as a teacher, F.

Pasteur spent them at École St-Esprit in Quebec, where he taught manual labour.

He had taken the courses then being held in Limoilou under the direction of F.

Georgius and had become competent in this field. This was to serve him later in

the various works of the provincial house.

In two places, Causapscal and Bagotville, brother Pasteur was director. It was a difficult five years. He wasn’t cut out to be a school principal and community superior. He himself confided to me that in one of these communities he had all his confreres in league against him. At least, that’s what he remembered. One wonders where the fault lies. Undoubtedly, the traits of his character and personality were at the origin of these conflictual situations. The fact remains that he saw fit to give his resignation to the provincial brother, who accepted it. As a good submissive inferior, he returned to the ranks and became a professor again for another two years, before receiving a lasting and definitive obedience at the provincial house of L'Ancienne-Lorette.

In two places, Causapscal and Bagotville, F. Pasteur was director. It was a difficult five years. He wasn’t cut out to be a school principal and community superior. He himself confided to me that in one of these communities he had all his confreres in league against him. At least, that’s what he remembered. One wonders where the fault lies. Undoubtedly, the traits of his character and personality were at the origin of these conflictual situations. The fact remains that he saw fit to give his resignation to the provincial brother, who accepted it. As a good submissive inferior, he returned to the ranks and became a professor again for another two years, before receiving a lasting and definitive obedience at the provincial house of L'Ancienne-Lorette.

The last 47 years of his life, brother Pasteur had

to spend them at the provincial house of Ste-Foy as a nurse, electrician,

commissionaire, factotum (jack of all trades) and retired. It is especially with this last slice of

life that the memory of brother Pasteur will remain in the memory of young brothers

and even the less young.

As a nurse he succeeded brother Hector Ruest and brother Norbert Lizée. He held this position for 22 years. How many merits are accumulated

in this task, if one considers that his dispensary and the rooms of the

infirmary were on the fifth floor and that, for five years, before the

installation of an elevator, he had to go up there with the meals of the sick.

Those he has cared for bear witness to his

dedication, precision and know-how. No doubt, they were sometimes reprimanded,

because brother Pasteur would often rebuke.

Woe to the novice who came to ask him for

syrup for a cold while, in the previous days, our nurse had seen him

strutting barefoot on the still fresh days of April or May. May.

He took everything seriously and wanted others

to do the same. Therefore, provincial superiors and master trainers had to take

into account the medical records of each of the subjects in formation. Still at

88, he remembered that a provincial superior had reproached him for not

mentioning that such a novice had a predisposition to tuberculosis: "Yet I

had written, he said, the statement of the doctor: candidate for

tuberculosis."

Some confreres disagreed with brother Pasteur on

how he chose doctors. These are criticisms that show that tradition is

maintained and that men have always opined either for Hippocrates or for

Galian. He sometimes invited leading physicians who, for the occasion, were

lecturers and gave sound advice on health care. I remember a Dr. Rainville in

particular. According to this specialist, the disease (cancer, heart disease,

etc.) does not take over a healthy organism (!), and it is breathing that keeps

an organism healthy. Still in the same line, he said: "The secret of

health is the sign of the cross: forehead back, belly back, shoulders

back!" Only remains in front is the chest, which must be inflated of pure

air.

Brother Pasteur was available 24 hours a day. I

remember that one night I had a shiver all over my body. I went up to brother

Pasteur, who must have wondered what I had, so much the teeth were slamming in

my mouth and I could hardly express myself. Without grumbling, he gave me an

electric cushion on which I slept the rest of the night and thus conjured up

what, in my opinion, looked like a very strong crisis of bile.

One Fall, he advised the brothers to get the

flu shot. Two confreres accepted the vaccine, and they were the only two who

had the flu! Some clever men claimed that the vaccine had to be given twice and

that, by giving it once, he had communicated the virus to them. In the small

world of L'Ancienne-Lorette, the brother nurse was more often subject to criticism, but never unkind. What remains

certain is that brother Pasteur left the memory of a dedicated, competent and

conscientious nurse. His little grumpy or preachy side does not take anything

away from him.

The last 47 years of his life, F. Pasteur had

to spend them at the provincial house of Ste-Foy as a nurse, electrician,

commissionaire, factotum and retired. It is especially with this last slice of

life that the memory of F. Pasteur will remain in the memory of young brothers

and even the less young.

As a nurse he succeeded FF. Hector Ruest and

Norbert Lizée. He held this position for 22 years. How many merits are accumu1s

in this task, if one considers that his dispensary and the rooms of the

infirmary were on the fifth floor and that, for five years, before the

installation of an elevator, he had to go up there with the meals of the sick.

Those he has cared for bear witness to his

dedication, precision and know-how. No doubt, they were sometimes admonished,

because F. Pasteur was a sermon in his hour.

Woe to the novice who came to ask him for

syrup for the cold while, in the previous days, our nurse had seen him

strutting barefoot on the still fresh days of April or May.

He took everything seriously and wanted others

to do the same. Therefore, provincial superiors and master trainers had to take

into account the medical records of each of the subjects in formation. Still at

88, he remembered that a provincial superior had reproached him for not

mentioning that such a novice had a predisposition to tuberculosis: "Yet I

had written, he said, the statement of the doctor: candidate for

tuberculosis."

Some confreres disagreed with F. Pasteur on

how he chose doctors. These are criticisms that show that tradition is

maintained and that men have always opined either for Hippocrates or for

Galian. He sometimes invited leading physicians who, for the occasion, were

lecturers and gave sound advice on health care. I remember a Dr. Rainville in

particular. According to this specialist, the disease (cancer, heart disease,

etc.) does not take over a healthy organism (!), and it is breathing that keeps

an organism healthy. Still in the same line, he said: "The secret of

health is the sign of the cross: forehead back, belly back, shoulders

back!" Only remains in front of the chest, which must be inflated of pure

air.

The F. Pasteur was available 24 hours a day. I

remember that one night I had a shiver all over my body. I went up to the F.

Pasteur, who must have wondered what I had, so much the teeth were slamming in

my mouth and I could hardly express myself. Without grumbling, he gave me an

electric cushion on which I slept the rest of the night and thus conjured up

what, in my opinion, looked like a very strong crisis of bile.

One fall, he advised the brothers to get the

flu shot. Two confreres accepted the vaccine, and they were the only two who

had the flu! Some clever men claimed that the vaccine had to be given twice and

that, by giving it once, he had communicated the virus to them. In the small

world of L'Ancienne-Lorette, the brother nurse was more often than in his turn

the target against which many arrows flew, but never murderous. What remains

certain is that F. Pasteur left the memory of a dedicated, competent and

conscientious nurse. His little grumpy or preachy side does not take anything

away from his merits.

Thanks to correspondence courses, brother Pasteur

was licensed in electricity. His authority was repeatedly used to electrify

various houses in the province. This is how, for example, he lived at Les

Éboulements and Rivière-à-Pierre. In the same vein, in the early 1950s, he

decided to install the intercom at the provincial house.

With the determination he was known to have,

he worked on his project for months if not years. The further

progress of the technique and the advent of electronics had to relegate to the

past so many of his efforts.

The house of L'Ancienne-Lorette, being located

near the Ste-Foy airport, necessitated to equip its bell tower and its bells

with red lamps. If a light bulb came out, it was brother Pasteur's responsibility to climb

the tower and replace the light bulbs. Still in his nineties, if he were

reminded of his former exploits, he would repeat: 'I would go again, but I am

not allowed to do so!" Audaces fortuna juvat!

Thanks to correspondence courses, F. Pasteur

was licensed in electricity. His authority was repeatedly used to electrify

various houses in the province. This is how, for example, he lived at Les

Éboulements and Rivière-à-Pierre. In the same vein, in the early 1950s, he

decided to install the intercom at the provincial house.

With the determination he was known to have,

he worked on his project for months if not years. The further

progress of the technique and the advent of electronics had to relegate to the

shadows what had cost them so much effort.

The house of L'Ancienne-Lorette, being located

near the airport Ste-Foy, was necessarily to equip its bell tower and its bells

with red lamps. If a light bulb came out, it was the F. Pasteur climbing up

there and putting everything back in order. Still in his nineties, if he were

reminded of his former exploits, he would repeat: 'I would go again, but I am

not allowed to do so!" Audaces fortuna juvat!

Who did not hear F. Pasteur speak of the

Paquin families did not know him fully. Yes, for 25 years, our brother was a

genealogist. Initiated to this science by his friend, F. Dominique Campagna, he

set to work and travelled through an infinite number of parishes, he wrote a

multitude of letters, he traced the marriage certificates of the Paquin

families. He organized a large movement that was to bring together all the

Paquins of Canada and the United States. A periodic bulletin reached the

families. He himself, at the age of 75, took up the pen and wrote the

"Little History of the Paquin Families in America".

On May 3, 1982, in the presence of two

witnesses, he signed an act in which he bequeathed to the Association des

familles Paquin Inc. 400 volumes of La Petite histoire, 30 notebooks of family

records, 40 to 50 notebooks of correspondence, 6 notebooks of archives, 6

volumes of descriptions of lineages, cartons of these same lineages, the book

of benefactors, not to mention flags, badges and films. And all this was the

fruit of a work pursued with the same relentless effort as he had undertaken

all things in his life.

Who did not hear brother Pasteur speak of the

Paquin families did not know him fully. Yes, for 25 years, our brother was a

genealogist. Initiated to this science by his friend, brother Dominique Campagna, he

set to work and travelled through an infinite number of parishes, he wrote a

multitude of letters, he traced the marriage certificates of the Paquin

families. He organized a large movement that was to bring together all the

Paquins of Canada and the United States. A periodic bulletin reached the

families. He himself, at the age of 75, took up the pen and wrote the

"Little History of the Paquin Families in America".

On May 3, 1982, in the presence of two

witnesses, he signed an act in which he bequeathed to the Association des

familles Paquin Inc. 400 volumes of La Petite histoire, 30 notebooks of family

records, 40 to 50 notebooks of correspondence, 6 notebooks of archives, 6

volumes of descriptions of lineages, cartons of these same lineages, the book

of benefactors, not to mention flags, badges and films. And all this was the

fruit of work pursued with the same relentless effort as he had undertaken

all things in his life.

Time of old age became a reality for brother Pasteur. The years of which Qoheleth said: "I do not love

them" (Qo 12:1). Closer to us, it was Lavoisier who, anticipating his

imminent death, wrote to his wife: I feel that I will not have to endure the

disadvantages of old age". Determined to live until his death, our

confrere fought so hard that he could fight against everything that this old

age brings. He pressed a rubber ball into his hands, pedaling on the spot while

reading the Bible (sic). On various occasions he was allowed to do internships

at the B.C. clinic in Montreal. When this permission was refused, he suffered

greatly because he believed that the struggle would have made him victorious

once again. Those who attended these fights assure that he thus saved himself

ten years of wheelchair. It’s still something, though.

It cannot be said that brother Pasteur was a sad or morose old man. Willingly, he accepted teasing, and his

colleagues knew it! In certain areas, such as liturgy, community life, and

dress, he held firm and defended his positions. He who wrote these lines, being

back in L'Ancienne-Lorette after having been away from it for three decades,

had the happiness to find brother Pasteur and to have with him long interviews

almost daily. He was then treated to speeches identical to those he had heard

thirty years earlier, and almost in the same words. What fidelity to oneself in brother Pasteur! When we parted, he said with a smile: "Tomorrow we will

address another theme." Sometimes he would look for his words, but on the

whole his memory had remained faithful to him and his mind was perfectly lucid

and had to remain so until the end.

He had remained himself, the one we had always

known; his legs alone betrayed him at times, his knees flogged, and he had to

move in a wheelchair for the last eight or nine years of his life. On sunny

days, he would appear in the community hall after breakfast. During the fine

summer days, he was on the gallery and rested in the swing.

A successful old age

A successful model of old age, this is how I

would be inclined to present brother Pasteur to confreres who knew him and to

those of future generations. And what prompts me to present it in this way is

that I have heard it repeatedly make a rereading of his life. He then recalled

the events of his past. Sometimes they were pure and simple failures. He knew

then how to confess his misfortunes and laugh. And this is what I found very

edifying.

"Every old man saw a tragedy", a

friend told me who visited hundreds of old people every month. It seems to me

that brother Pasteur escaped this rule. He looked back on his past to take stock

of it with complete serenity.

Came for our F. Pastor the

years of old age, the years of which Qoheleth said: "I do not love

them" (Qo 12:1). Closer to us, it was Lavoisier who, anticipating his

imminent death, wrote to his wife: I feel that I will not have to endure the

disadvantages of old age". Determined to live until his death, our

confrere fought so hard that he could fight against everything that this old

age brings. He pressed a rubber ball into his hands, pedaling on the spot while

reading the Bible (sic). On various occasions he was allowed to do internships

at the B.C. clinic in Montreal. When this permission was refused, he suffered

greatly because he believed that the struggle would have made him victorious

once again. Those who attended these fights assure that he thus saved himself

ten years of wheelchair. It’s still something, though.

It cannot be said that the F.

Pasteur was a sad or morose old man. Willingly, he accepted teasing, and his

colleagues knew it! In certain areas, such as liturgy, community life, and

dress, he held firm and defended his positions. He who wrote these lines, being

back in L'Ancienne-Lorette after having been away from it for three decades,

had the happiness to find the F. Pasteur and to have with him long interviews

almost daily. He was then treated to speeches identical to those he had heard

thirty years earlier, and almost in the same words. What fidelity to oneself in

the F. Pasteur! When we parted, he said with a smile: "Tomorrow we will

address another theme." Sometimes he would look for his words, but on the

whole his memory had remained faithful to him and his mind was perfectly lucid

and had to remain so until the end.

He had remained himself, the one we had always

known; his legs alone betrayed him at times, his knees flogged, and he had to

move in a wheelchair for the last eight or nine years of his life. On sunny

days, he would appear in the community hall after breakfast. During the fine

summer days, he was on the gallery and rested in the swing.

A successful old age

A successful model of old age, this is how I

would be inclined to present the F. Pasteur to confreres who knew him and to

those of future generations. And what prompts me to present it in this way is

that I have heard it repeatedly make a rereading of his life. He then recalled

the events of his past. Sometimes they were pure and simple failures. He knew

then how to confess his misfortunes and laugh. And this is what I found very

edifying.

"Every old man saw a tragedy", a

friend told me who visited hundreds of old people every month. It seems to me

that the F. Pasteur escaped this rule. He looked back on his past to take stock

of it with complete serenity.

Brother Pasteur experienced very few health

accidents and was able to carry out his activities until advanced old age. With

the exception of liver disorders, which necessitated the removal of the

gallbladder some 40 years ago, it can be said that he was a "healthy"

man. He had to rely on the good care of the nurses when his legs failed. He was only really sick during his very last days, when a renal

failure occurred at his home, which led to heart failure. This is what he was

to die of at the dawn of April 17, 1996.

Brother Louis-Régis Ross, s.c.

The F. Pasteur experienced very few health

accidents and was able to carry out his activities until advanced old age. With

the exception of liver disorders, which necessitated the removal of the

gallbladder some 40 years ago, it can be said that he was a "healthy"

man. He had to rely on the good care of the nurses when his legs refused to

wear it. He was only really sick during his very last days, when a renal

failure occurred at his home, which led to heart failure. This is what he was

to die of at the dawn of April 17, 1996.

F. Louis-Régis Ross, s.c.